Series Part 3: On Scaling Up

From shipping frozen dumplings to bringing in the USDA to automating production.

This is part three of a special collaborative feature with Dumpling Club’s Cathay Bi— excerpted from the second print edition of the Above the Fold zine—about what it takes to start and operate a dumpling business in the U.S.

In this installment, learn about the decisions that makers need to make if they want to sell nationally either direct to consumers or via national retailers—and produce dumplings in quantities to match. Inside, you’ll find:

Kachka’s Bonnie Morales on the challenges of shipping frozen dumplings

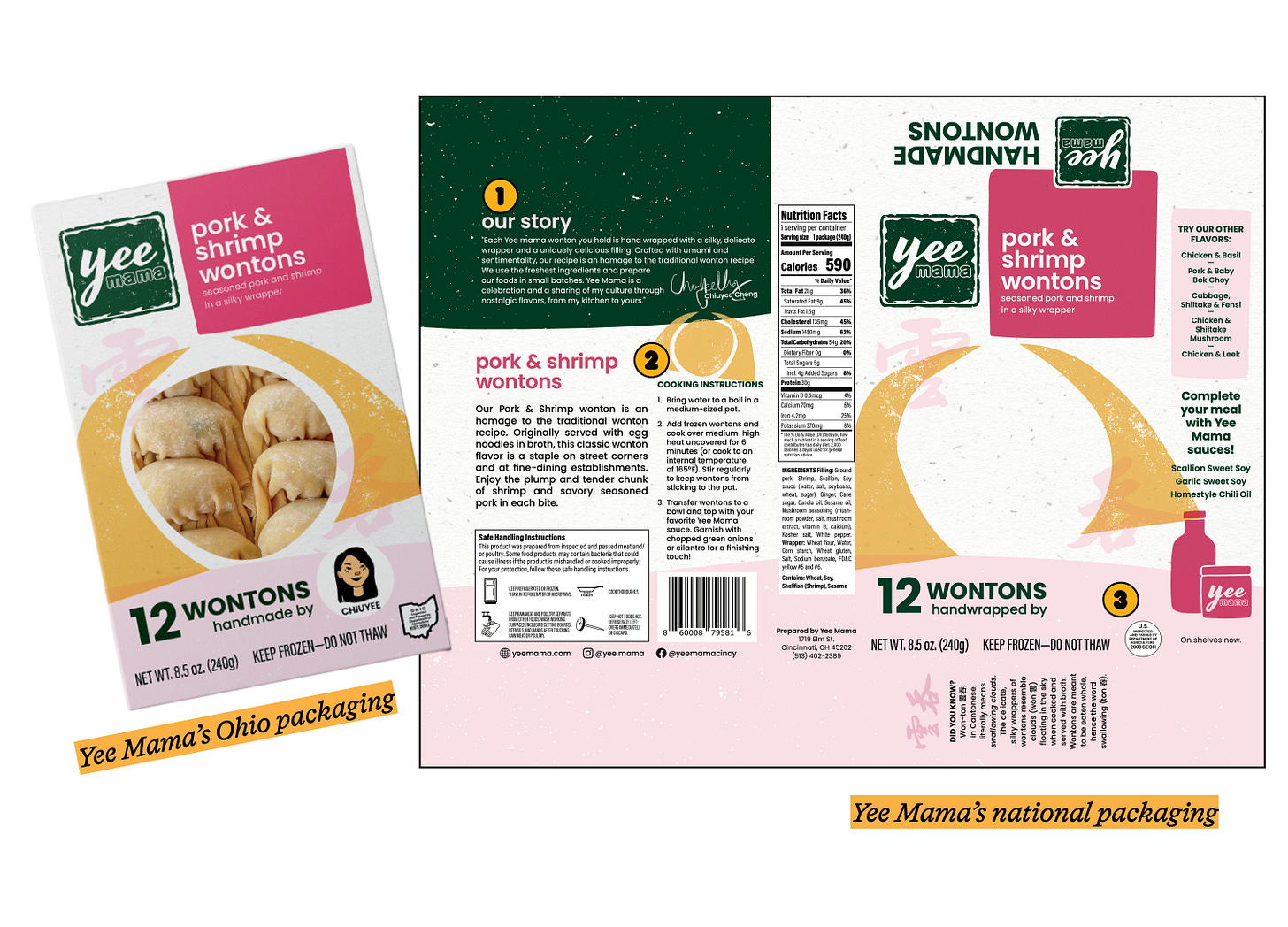

Yee Mama’s Dora Cheng on what it takes to get USDA certification

Himalayan Dumplings’ Kyikyi (read her Above the Fold interview!) on the process of automating her hand-pleated momos

Shipping Frozen is a P.I.T.A.

Bonnie Frumkin Morales, who runs Portland, OR-based restaurant and dumpling company Kachka, tested national shipping and has since pulled back. Here's why.

“In the shipping world, frozen is notoriously challenging, and ice cream is considered to be the hardest. The thing that ice cream has going for it is that it’s really dense, so it keeps itself cold a little easier; dumplings have a lot of

surface area—if they melt at all, they’re gonna stick to each other, and they’re ruined.

If FedEx or UPS has a delay of some sort and the product doesn’t get there in time, it’s not just that that customer is upset that the product didn’t come—it’s now a ruined product, and they still need it, so then you have to re-ship it. In my experience, 80 to 90% of the time FedEx or UPS doesn't reimburse you for that missed delivery because it’s probably “weather related,” which is outside of their control. Even if 75% of the time everything’s fine, if the other 25% of the time you have crazy delays and ruined product, you’ve now squandered any profit you might have gotten from it—if not started to lose money.

On top of all of this, just like with ice cream, you cannot ship dumplings without dry ice. A lot of carriers won’t take it, or you have to declare it. And there’s also handling—you have to have special gloves and special equipment. If you’re thinking about dry ice as another logistics issue, the stuff evaporates over time, so you can’t just store dry ice at your facility unless you’re a shipper.

So you have to do your shipping shipments once a week, and order dry ice just in time for that. We do not ship nationally right now—the costs are pretty prohibitive, unless you really scale up.”

Bringing in the U.S.D.A.

All packaged foods must follow state requirements around nutrition labels, the way ingredients are tracked and stored, and even product names. Dumplings present additional complexity, since makers must properly handle raw meat and/or seafood. And if you want to sell wholesale across state lines, the USDA needs to get involved. Dora Cheng of Ohio-based Yee Mama went through the process of obtaining a wholesale license and getting packaging and labels approved at both the state and federal level with a goal of bringing her dumplings into retail stores nationwide. It took almost a year, requiring support from a packaging designer, HACCP plan expertise, and plenty of back and forth with regulators. Below is a small handful of the roadblocks and surprises she navigated.

1. “[The USDA] guidebook defines Cantonese seasoning as ‘...mildly seasoned with sugar, salt, wine, and spices.’ Because that definition has wine in it [and our product doesn’t], we can’t call our product Cantonese.”

2. “For the words saying ‘ready to eat in six minutes’ because you boil them and it’s ready in six minutes, [we had] to do a study and hire someone to provide the proof.”

3. “Every time we make our product, there’s an inspector there. People are always shocked to hear that, but they do send people to our kitchen every day to check our paperwork.”

When It’s Time to Automate

After hand-making over 250,000 momos, Kyikyi of Beaverton, OR-based Himalayan Dumplings started experiencing chronic pain in her hands, arms, and fingers. After launching a crowdfunding campaign, she purchased a top-of-the-line dumpling machine from Taiwanese company Anko, which cost $70,000 plus another $5,000 in training. She says the investment was worth it, but not without a steep learning curve.

“I’ve had a couple people tell me, so-and-so switched to a machine and it just doesn’t taste the same. And I would scratch my head and think, why wouldn’t it taste the same? If it’s the same recipe, shouldn’t it taste the same in theory? Once I got the machine, I realized that there are some mechanical implications and influences that happen, such as the heat being generated from the machinery, and other things that we don’t generally think about when we’re hand-making dumplings.

It was a trial-and-error process that cost me thousands in dumplings. For three or four months, I had to throw away so much product because I couldn’t figure out why my dough was changing once I put it into the machine or why the viscosity of my filling was changing.

I was adjusting the recipe left and right, and freaking out: Here I am paying the most money I’ve ever paid in my life; how come it didn’t work just right out of the box? I took a step back and went deep into the mechanics of the machine, and eventually was able to get very close to the original recipe.

Ironically, when I was hand-making dumplings, a lot of people already assumed I was using a machine a because I had gotten good at being uniform about my pleating. [Since automating] the feedback has never been better, and I think it’s partly the consistency. The machine can produce a scale and level of consistency that would be hard to achieve with hands no matter how good we are.

There was a lot of deliberation in making sure that my customers and my cafe guests will see absolutely no difference [between hand-made or machine-made dumplings] but to the contrary—they will always get equal portions of the dumplings they are paying for.”

Like what you read? Subscribe to Above the Fold and Dumpling Club for more! Next week: Parting thoughts and words of wisdom.

*Note: Interviews and surveys were conducted between April and July of 2024. Information is accurate as of that timeframe; in the world of dumplings and business things are, of course, subject to change.