Series Part Two: On Business Models & Financing

Advice on crowdfunding, balancing revenue streams, and deciding between the restaurant vs. packaged goods route.

This is part two of a special collaborative feature with Dumpling Club’s Cathay Bi— excerpted from the second print edition of the Above the Fold zine—about what it takes to start and operate a dumpling business in the U.S.

In this installment, learn about how dumpling makers select their business models and make funding decisions. Inside, you’ll find:

An overview of how makers chose their business models

A candid recounting from Jessica & Trina Quinn of Dacha 46 on what it’s like to crowdfund

Insights from Irene Li of Mei Mei on what it’s like to operate multiple business models at once

1. Getting started: How did you land on your business model?

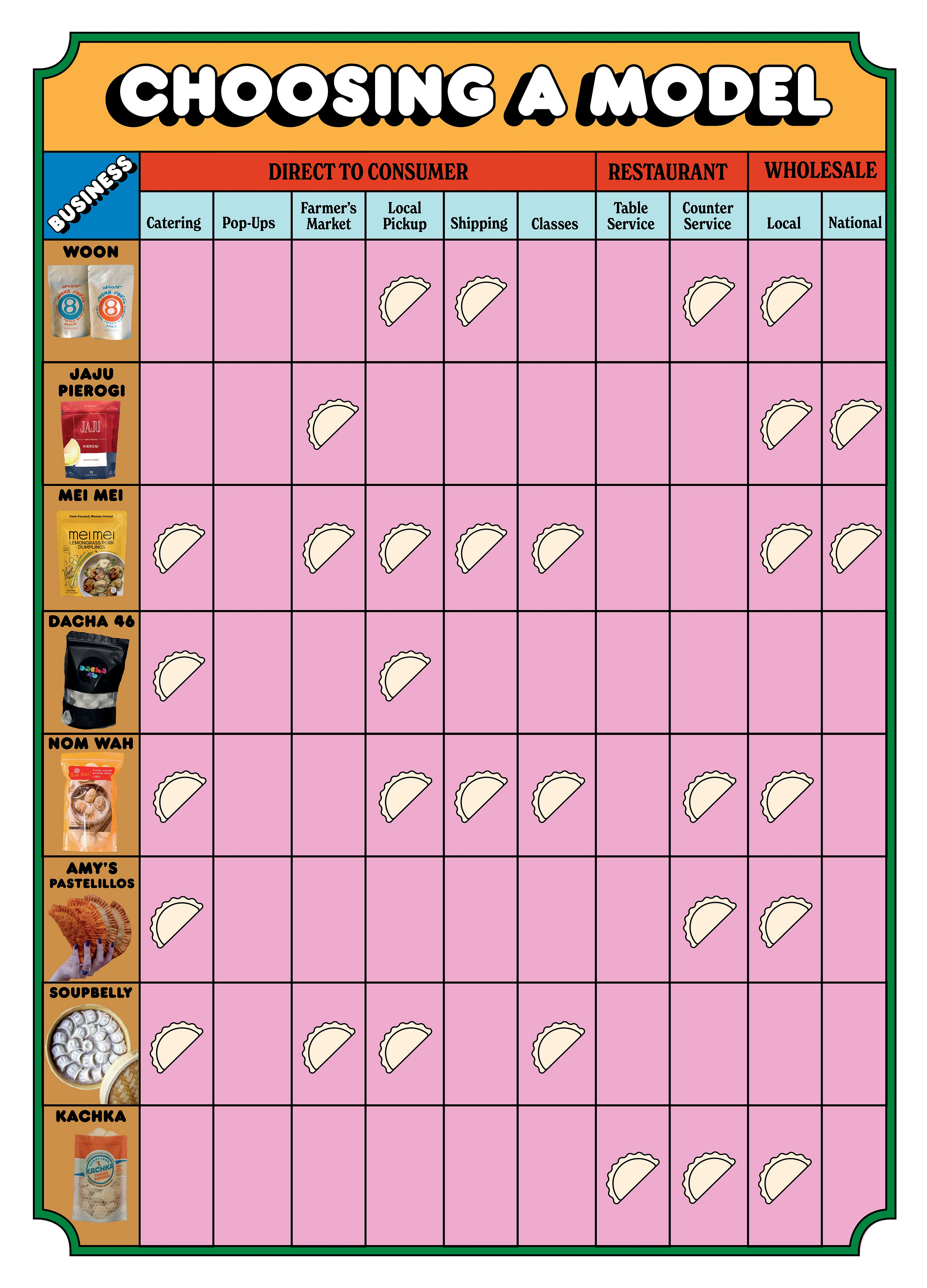

When starting up, there are some big decisions that dumpling makers need to make: Where do you want to sell your dumplings— locally or nationally? Do you want them to be ready to eat or for customers to cook them at home? How will you finance those early days: By bootstrapping yourself, or by taking in outside investment? Most, like those shown here, rely on a mix of strategies.

Keegan Fong, WOON (local pickup, shipping, counter service, local wholesale)

“I built the business plan with the idea to scale it into a packaged goods business eventually. However, in the plan, it was supposed to happen at Year 5. COVID fast forwarded that timeline to Year 2.5. In a way, it forced us to learn quickly.”

*note: Woon has temporarily suspended dumpling operations since taking the survey

Casey White, JAJU PIEROGI (farmers’ markets, national wholesale, local wholesale)

“It’s really important to diversify your revenue streams in food and specifically CPG, there is a lot of cost associated to doing business, so the more channels, the better to mitigate risk.”

Irene Li, MEI MEI (catering, farmers’ markets, local pickup, shipping, classes, and local and national wholesale)

“The most important learning here is to be careful of ‘scope creep.’ It's easy to get excited by shiny things, but if they don’t make money or require too much capacity, they ultimately eat into what actually drives the business. Balancing saying yes with saying no is a real art!”

Jessica & Trina Quinn, DACHA 46 (catering, local pickup)

“We’ve decided that a restaurant is not what we want. Our business focus now is to become a prepared foods/general store and cafe/bakery during the day. We’ll still do custom orders, catering and events, but in a place where we can actually showcase our pelmeni.”

Barbara Leung, NOM WAH (catering, local pickup, shipping, classes, counter service, local wholesale)

“We’ve diverted from only having a restaurant to also having a USDA facility to allow for wholesale, and to be able to siphon the workflows. Drawback has been lost revenue and financial investments/cost.”

Amy Rivera Nassar, AMY’S PASTELILLOS (counter service, local wholesale)

“I started as a pop-up concept then turned into a small takeout brick-and-mortar. When you do pop-ups, you have limitations on reach. With a home base, people can find us and try our food more easily.”

Candy Hom, SOUPBELLY (catering, farmers’ market, local pickup, classes)

“I started doing mostly frozen dumpling pickups and pop-up combinations 3-4 times a month. It wasn’t sustainable because of burn out (especially as a one-woman operation). I tried to add balance with workshops and special events to cut down on the number of pop-ups.”

Bonnie Morales, KACHKA (table service, counter service, local wholesale)

“For us, there’s a really strong tie between food service and what we sell in packages, so I can’t see a world where somebody can buy our dumplings at a grocery store in an area where they couldn’t also go visit us and eat our dumplings here in our restaurant.”

The Reality of “Doing It All”

Mei Mei started in Boston as a food truck in 2012 and today is a dumpling factory and classroom. Co-founder Irene Li breaks down their margins (including those of their now-closed cafe).

“Having diversified revenue streams sounds good. It sounds great to say, hey let’s do classes AND cafe service! But then you have to do classes and cafe service. In our case, the property shaped how we crafted the business. It’s a 5,500-square-foot warehouse in Southie in Boston. But the identity is more of a brand flagship or factory shop.

We practice open book management, which means we share our financials with our team every quarter. We don’t manage separate P&Ls, but we do have separate revenue goals for each pillar of our business. Generally we see that classes and events have the lowest cost and highest margin. COGS (cost of ingredients) are minimal and labor is just the instructor (you cook your own food). They’re also so fun and memorable.

On other hand, the cafe has the highest cost and lowest margin. Labor cost is high and COGS are higher too because you have to have a complete menu even if people only usually order a couple items. This means if we ever have a request for a private event, we’re going to close the dining room; the margins are better. But it’s a tough choice because diners expect restaurants to have regular hours and can stop coming if they don’t know when we’ll be open.

Packaged dumpling sales land somewhere in the middle: lower margin than classes but better margins than the cafe. The numbers also tell us that we make significantly more profit selling direct to customers as opposed to wholesale. In fact, wholesale to major brands like Whole Foods is practically impossible for us because they take such an exorbitant cut.

But we have found some success selling to smaller, local grocers and we are growing that part of the business. We had a great first year and we’re breaking even. But I don’t take a salary and neither do my two business partners, Alyssa and Annie.”

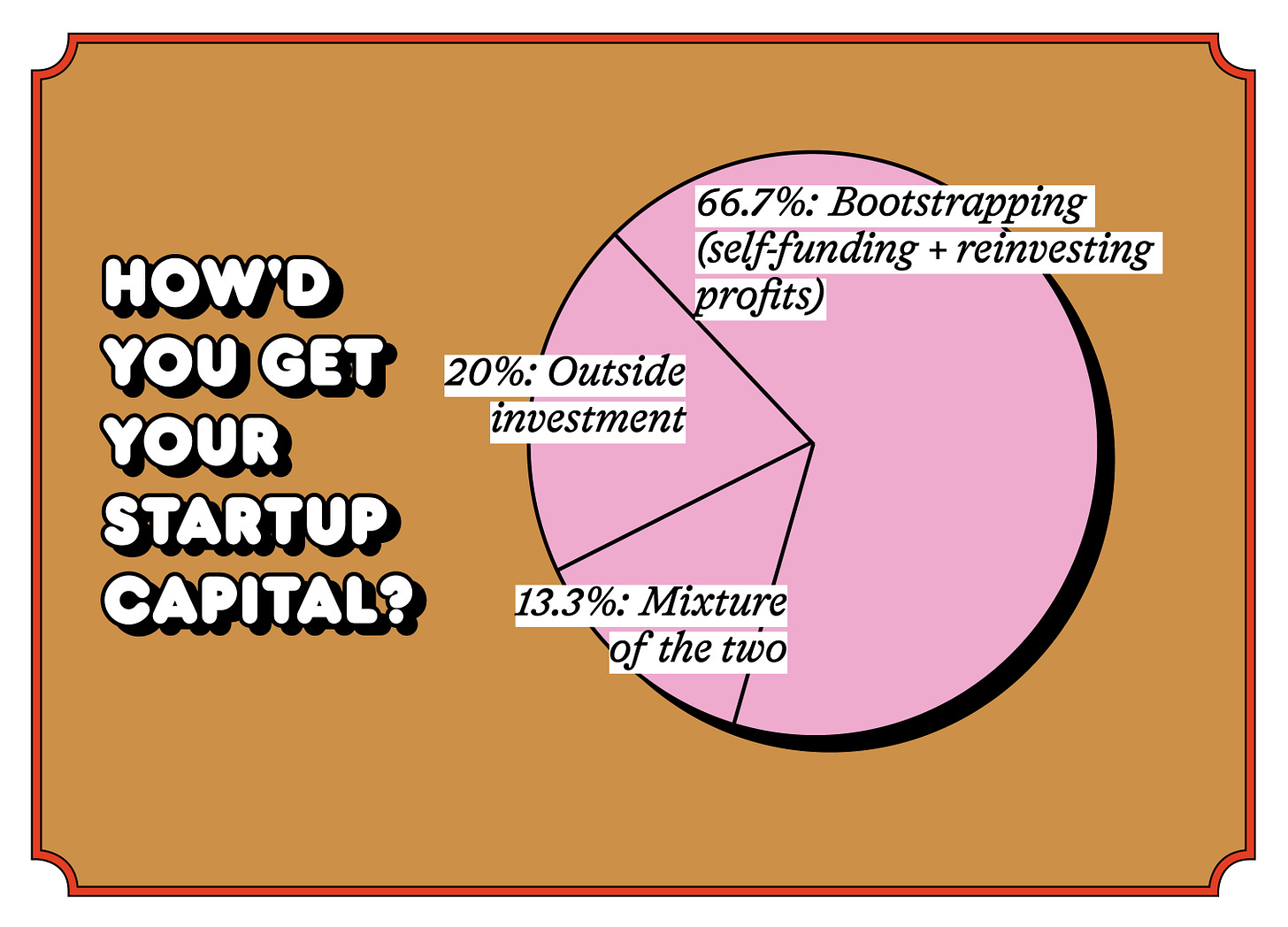

2. Getting funded: How’d you get your startup capital?

The Gift and Curse of Crowdfunding

In 2021, Dacha 46’s Jess & Trina Quinn launched a Kickstarter campaign to fund their Brooklyn-based business with a $40K goal. Ahead, they share their experience.

“We were so naive, to think about the amount that we asked for. After Kickstarter collected their fees and taxes, it was around 30-something. [In hindsight,] we would have started a pitch deck a lot earlier and we would’ve started taking investor meetings. We can say that now three years in, but we wouldn’t have known—we didn’t know what a pitch deck was.

We couldn’t wrap our heads around what it really takes to start a business in New York City. When we were raising the money, we thought that that would give us six months of operating costs to open a place, because we were factoring in [a place that would be] like $5,000 a month to rent. When we started actually messaging different commercial kitchens, they were like, Yeah, you know, it’s, you know, 5K a month and it’s $250,000 in key money. We didn’t know what ‘key money’ was back then.

One of the lessons that we’ve learned is that there’s no shame in asking for help. And there’s definitely no embarrassment about not knowing something, because the only way you’re gonna learn is by asking. We had a friend that helped us produce the visuals and the graphics for our pitch deck. We had another friend that helped us with the numbers.

We are still stressed about the Kickstarter because [we still have to fulfill the rest of] the rewards. Right now, whatever money we make from Dacha is all we have, but we also have such devoted people that have helped with the Kickstarter. It’s just this sense of obligation where we just wanna fulfill everything, and we just can’t until we get the brick-and-mortar [open].

[But] every very little bit helped us continue. Without the Kickstarter, we would not be functioning right now. So, as much as we wish we went a different route, we’re still happy we did it—because without it, there would be no Dacha 46 right now.”

Like what you read? Subscribe to Above the Fold and Dumpling Club for more! Coming up next week: The tools and strategies that makers use to scale their businesses.

Note: Interviews and surveys were conducted between April and July of 2024. Information is accurate as of that timeframe; in the world of dumplings and business things are, of course, subject to change.