Interview #5: Brandon Blumenfeld's Kreplach

"The lifeline doesn’t exist anymore—the person whose recipe I’m using isn’t here."

In 1921, Joseph Rosenbloom, a tailor, left his home in Poland for America. He put down roots in Pittsburgh, where he introduced his family to kreplach: an Ashkenazi Jewish dumpling, typically filled with meat, that’s traditionally consumed during the Jewish High Holidays and has origins both in Italian pasta-making and Central Asian manti1.

One century later, in early 2021, his great-grandson Brandon Blumenfeld launched a kreplach business in Pittsburgh called Little Tailor Dumplings. Blumenfeld’s kreplach are a reimagining of his great-grandfather’s, incorporating his professional background as a chef working at restaurants like Momofuku Noodle Bar and Franny’s in New York as well as several Pittsburgh restaurants (most recently Tryp by Wyndham in Lawrenceville, where early versions of his kreplach appeared on the menu). When we first spoke in early April, Brandon was selling his kreplach directly through Instagram via a donation-based system. Since then, his dumplings have made it onto local store shelves at shops like Bryant Street Market in Highland Park.

Below, learn about Brandon’s experience reimagining his great-grandfather’s recipe, plus his favorite way to eat them (hint: it involves mustard). If you’re feeling hungry from this interview (and also ready to roll up your sleeves), there’s a kreplach recipe from Pasta Social Club’s Meryl Feinstein with your name on it at the end.

Before fully diving into the origins of the name Little Tailor, I would love to hear about the business itself. It’s pretty new, right?

Yeah, very new. I had messed around over the past couple of years at some restaurants that I was running, making kreplach and putting them on the menu and getting a kick out of using a family recipe. But early on in the pandemic, I was kind of freaking out because I lost my job and was trying to find a way to generate an income for myself without working in a restaurant. I decided to make a batch of these kreplach. As I was eating them with my now-fiancée, I was thinking, “Wow, these are making me feel better in some way, and it might be cool to try to focus on making more of these and seeing if people are interested in it.” The thought was to create a product that was approachable, something you might find in the frozen food aisle of your local grocery store, with a family story and history that people might be able to connect to.

Can you tell me more about The Little Tailor and the significance to the name?

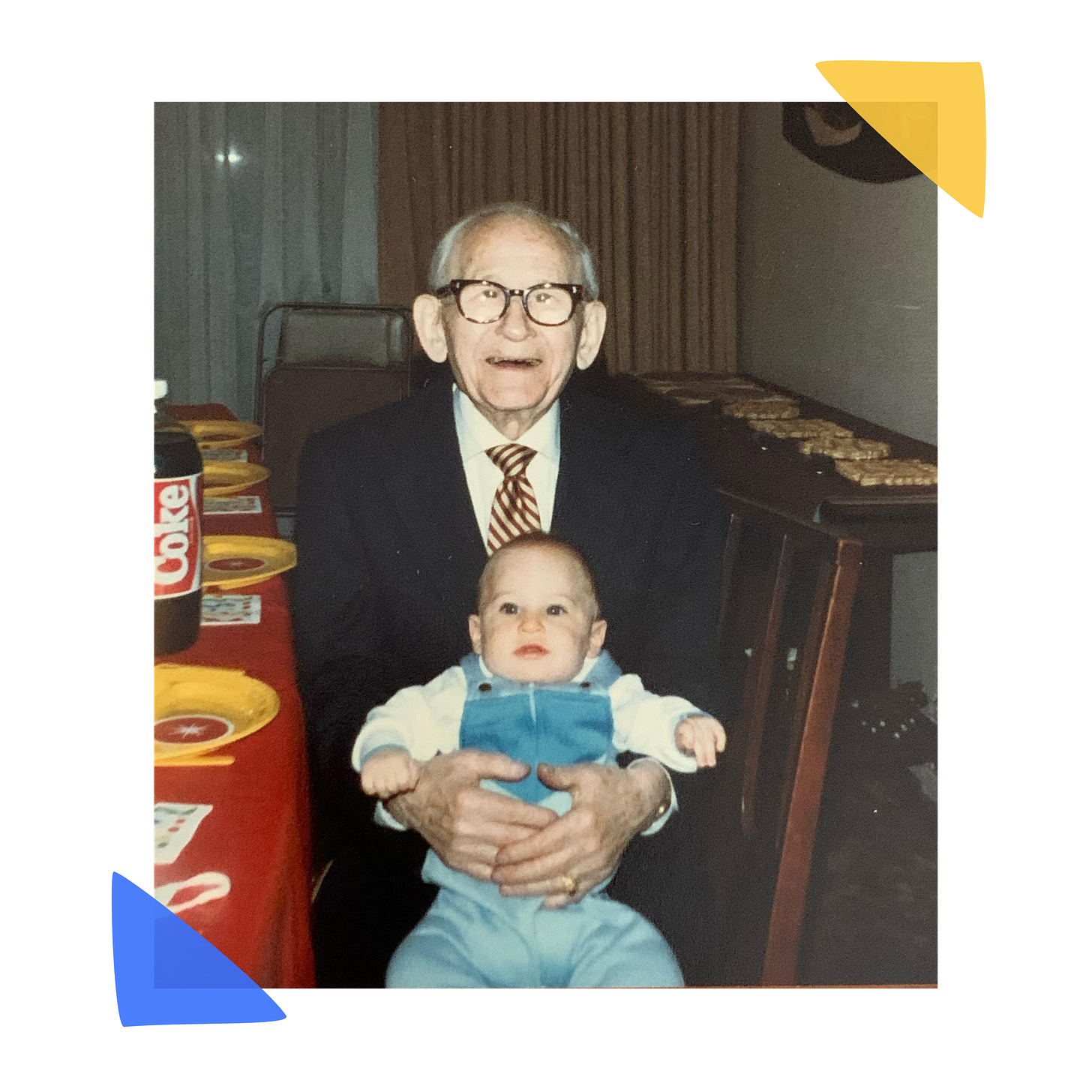

My great-grandpa Joe passed away when I was 2 years old. So we did meet, but unfortunately I have no memories of eating his kreplach—but it is a recipe that was his that has been passed down. I had known that he was a good cook; my mom and my aunt would make his recipes, but I never really focused on any of our family recipes too much. Then a few years ago, an article was written here in Pittsburgh about “The Little Tailor’s” dumplings. Someone my mom followed on Facebook had reached out looking for immigrant stories and recipes, and my mom got involved and talked about my great-grandfather and his kreplach. When we were doing interviews for that project, it really kind of steered the ship in a direction where I became very interested in our family recipes and digging deeper into our family tree and background.

So it wasn’t until that project that you actually started to try to make kreplach yourself?

Yeah, that’s correct.

What was that process like in the beginning, learning to make them?

In the beginning, it was a little frustrating because my background had been trying to work in the best restaurants and always having someone teaching me. I was like, “If I’m going to figure out how to do this, I really need to figure this out for myself,” because essentially, the lifeline doesn’t exist anymore—the person whose recipe I’m using isn’t here. I can’t ask them questions. I can’t do it the way that I had been trained to cook. Through talking to my mom and some other family members, I was able to piece together the way that he did it, and the ingredients that he used. My mom actually has a few items of his, including his mixing bowl and his rolling pin. And so that helped me to connect more, digging deeper into my imagination and embracing this feeling and connection to him even though he wasn’t there. From there, I became interested in figuring out not only how to make his dumplings but also how to use the knowledge and technical skills that I have from all of my experiences in making a version of his dumplings that I felt he would be proud of, and probably get a kick out of.

How would you describe what they have evolved into?

Traditionally, and with my great-grandfather’s recipe, the dumpling dough was very simple—there’s no measurements really, but he used all-purpose flour, egg, and water. He didn’t roll it out super-duper thin, and they were a bit chewier. So my mind kind of wandered, wondering how I would make a really tasty, chewy dumpling dough not necessarily using only flour, egg and water, something that might be a bit more technically involved and use my background in pasta-making. I added semolina flour to the dough, which is not traditional for an Eastern European dough. His filling was just ground meat, grated raw onion, salt and pepper and that was all. I add vegetables and herbs and some spices.

How much have your kreplach changed since you started experimenting early on?

In general, I would say, the shape has changed a little bit. My great-grandfather’s were literally either just pinched into triangles or crescent moons. I don’t think he spent a whole lot of time trying to make them uniform or anything like that. I had, at points, when I was in the restaurant industry, been making them more triangular and crescent moon-shaped. I was having a lot of issues with them breaking, because there are these stray edges and with the dough being brittle, we were running into an issue of them breaking when people were handling them, or going from the raw state into the frozen state and getting stuck together. By giving it a little more definition and folding it in the way that I’m currently doing it, I felt that people could see the value in paying for these a little bit more. It was kind of utilitarian and also an aesthetic thing that I was going for.

For the line of frozen dumplings, how many styles will you have?

In the beginning I was throwing a bunch of stuff at the wall and seeing what would stick. I think also in this day and age, social media and marketing, I thought it would be cool to have a bunch of different flavors, and a bunch of different colors, and I was constantly coming up with different flavors that I thought people could get excited about. I tried using different vegetable purees in the dough to create different colors, and then I re-honed it back. At least right now, I wanted to really kind of perfect some flavors that I thought would really be marketable and things that people could easily identify. I’m focusing on a meat one and a vegan one. The vegan filling is a combination of beets, mushrooms, herbs, and spices. And the meat one we’ve settled into is ground beef, and it has a lot of aromatics. I make a sofrito-like mixture out of cooked roasted vegetables that I use as a shmaltz for the fat.

How many are you making a week?

On average, about 30-60 dozen. I’m using pretty much only equipment that someone would have at home or at a small restaurant. I’m using a KitchenAid with a pasta roller attachment on it. I’m using a cookie cutter to cut all of the dough out from the sheets that I make, and filling all of the dough by hand and forming them by hand. It’s definitely time-consuming for myself. But I am really trying to hone in on the quality control process and work out the recipes so that later on down the line it’s a fail-proof process.

Have you taste-tested these with your family since? If so, what’s the reception been like?

So, my family has all gotten a lot of taste-testing throughout this entire process. Even throughout the very infancy stages, they’ve come to the restaurant that I worked at where I was serving more of a traditional version very similar to the recipe that he was using. At first there were definitely people from an older generation that thought that they were tasty but weren’t the kreplach that their parents made or that they ate when they went to a Jewish deli. But they were excited that I was reimagining and revisiting our culture’s food. My grandmother was really excited.

When you are off the clock, do you have a favorite dumpling you like to make for yourself or order from a specific place?

I’ve been eating the fried pork dumplings from The New Dumpling House in Squirrel Hill since I was a child. They’re made with a homemade dough that’s really thick and chewy, and there’s something about them that I can’t get enough of. The other dumpling I gravitate to, at least here in Pittsburgh, is at a Polish diner called S&D Polish in an area of Pittsburgh called the Strip District. They make amazing pierogis, and they also serve borscht that has little dumplings2 inside them. Those are the dumplings that I crave when not eating kreplach. But admittedly, I eat a lot of kreplach these days (laughs).

Do you have a favorite way to prepare the kreplach?

My favorite is pan-fried. It’s not necessarily the way that my family would eat them, my family would strictly eat them in chicken soup with matzo balls and kreplach, or just kreplach, but pan-frying them and dipping them in mustard is my favorite way that I’ve tried them.

Last question: Do you have any go-to music when you are in the dumpling folding zone?

Yes, I actually do. I do find myself listening to a lot of Jimi Hendrix when I make a lot of dumplings, something that has really high speed and a lot of finger picking—whenever the musician is really going all out with whatever instrument they are playing, I feel like I work a little bit quicker. There’s a lot of Jimi Hendrix, a lot of MF Doom, a lot of jazz. The Mahavishnu Orchestra, that’s definitely a band that gets played a lot.

Recipe: Meryl Feinstein’s Rye Kreplach with Caramelized Onion, Potato, and Mint

While I also come from an Ashkenazi Jewish lineage, kreplach aren’t in the Mennies family Jewish recipe canon—my cooking memories with my Grandmom Eve are tied to multi-day gefilte fish extravaganzas. But when I told my grandmother that I was working on this newsletter, she told me of kreplach made by the mother of her dear friend Judy (who we called “Aunt Judy” growing up). “The minute she came up north she had to go ahead and make those,” she told me. “They were excellent. We always said, ‘Judy, make sure that you have the recipe!’ I’m not sure if she ever did.” Long story short, in spite of Judy’s son Larry incredibly graciously going on a wild goose chase on my behalf, the recipe has not yet been uncovered (thank you so much for trying, Larry!).

Instead I bring you these rye kreplach from Meryl Feinstein of Pasta Social Club, which occupied a meaningful occasion in my family—they were the first thing I cooked together with my parents and sister after finally seeing them after over a year apart as a result of the pandemic. We used the dough from this recipe and the caramelized onion, potato, and mint filling from this one, which happened to fit best with the ingredients we had on hand. The recipe combines a thin, sturdy dough with a pierogi-like potato filling—we boiled ours and then pan-fried them and dipped them into yogurt. My parents’ dog Dottie really, really wanted one (and it was mean of me to take this photo but I couldn’t help it).

If you’re seeking something a bit more decadent, Feinstein’s Food 52 variation, created in collaboration with Jake Cohen of the book Jew-ish, includes chopped lox in the filling as well as a chili oil drizzle. And if you’re looking for something meatier, Basically has a good-looking one (which, caveat, I have not personally tried, but something tells me that Dottie would be jonesing for those, too).

Above the Fold was created by Leah Mennies. Logo + design elements by Claudia Mak.

The above interview was condensed and edited. Interview subjects are paid an honorarium for taking the time to share their knowledge and experience.

This article by Shulie Madnick in The Washington Post references food scholar Claudia Roden’s research into the topic for The Book of Jewish Food:

In her 1996 “The Book of Jewish Food,” Egyptian-born Claudia Roden wrote that Jews were making pasta in the ghettos of Germany through contact with their brethren in Italy, with whom they had trade and rabbinical connections, in the early 14th century.

Ashkenazi and Sephardic weave and intersect in Roden’s story of how sweetened cheese-filled pasta reached Polish Jewry: “Pasta came to Poland as a result of Italian presence at the royal courts and also by way of Central Asia. That may be why the cheese kreplach, sauced with sour cream, owes more to Turkish-Mongolian manti with yogurt poured over than to Italian ravioli or cappelletti.”

A small Polish dumpling called uszka