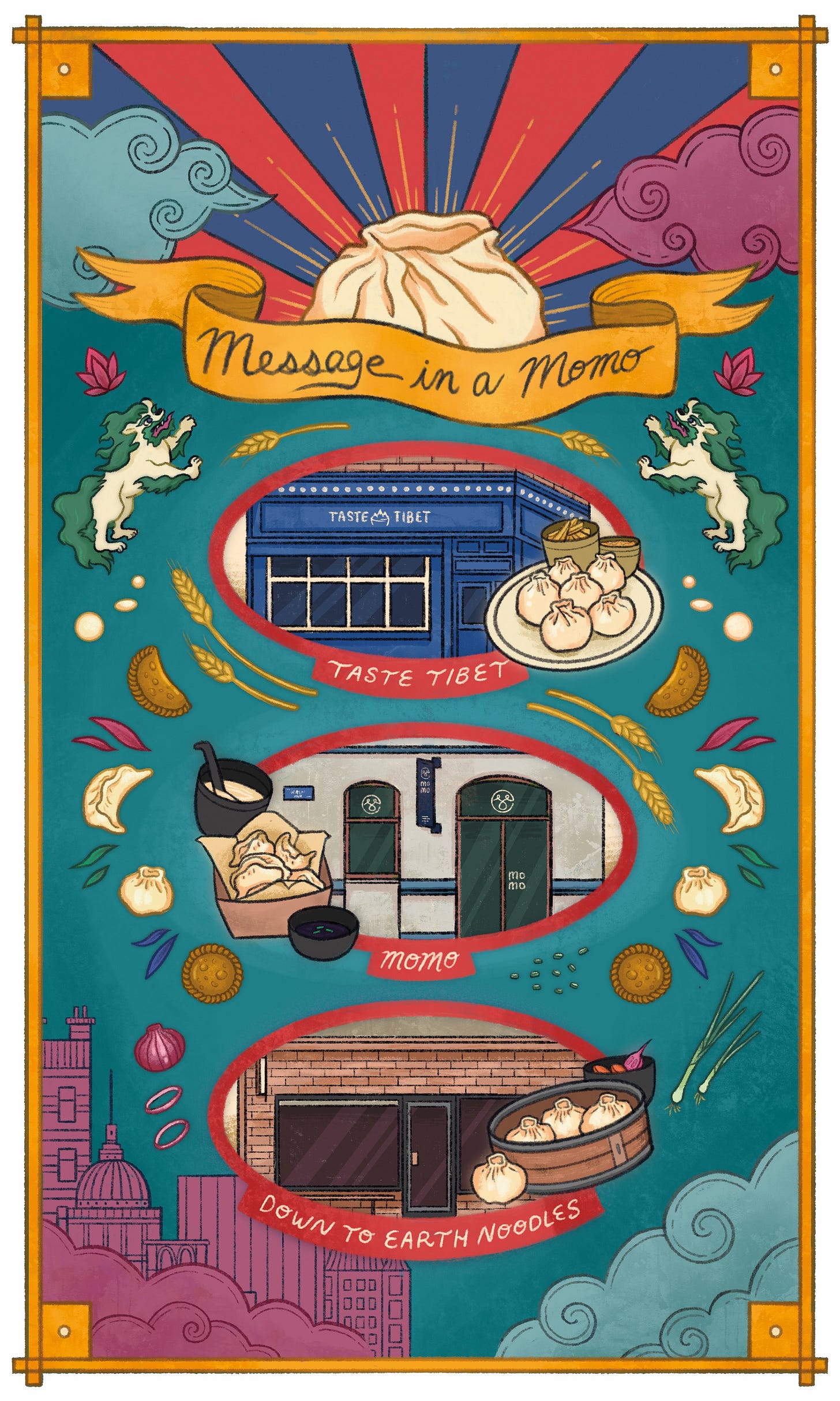

Message in a Momo

Sharanya Deepak details the resilience and adaptability underpinning the delicious food at Tibetan momo businesses located in Oxford, Brussels, and Cologne.

Welcome to the Above the Fold! The below feature is excerpted from the brand-new print edition of Above the Fold. For a hard copy that you can revisit from your coffee table/backpack/bookshelf whenever the mood strikes—plus much more!—order Issue 1 today:

For readers based in Canada, the UK, or Europe: You can snag your hard copy via Antenne Books. If you’re not in one of those locations but are interested in a copy, shoot me a note or comment and I’ll see what’s possible!

Message In a Momo

by Sharanya Deepak | Illustrations by Tenzin Tsering

Because of how many momos are eaten between India, Nepal, and Tibet, the genesis of the dish is always up for debate. But this dumpling’s origins are in Tibet, where communities have prepared and steamed them over communal fires in the cold valleys of their country for centuries. In Tibet, momos were traditionally stuffed with vegetables and yak meat. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the dish migrated with Newari traders to Nepal as they traveled between there and Tibet. When momos reached Nepal, yak meat became substituted with mutton and buffalo meat, and for vegetarian Hindu Nepalis, eventually vegetables like potatoes, spinach, and cabbage.

Following the Chinese seizure of Tibet in 1959, momos—like Tibetans—have traveled all over the world, particularly to India through Nepal and Bhutan. In New Delhi, where I was born and raised, the momo is perhaps the most-consumed street food in the city, sold by cooks of Tibetan, Nepalese, and Indian origins. (It’s also taken on a life of its own in the city, where it is put into a tandoor, stuffed with masala paneer, fried and put inside a burger for “moburgs,”and filled with molten chocolate.)

When I moved to Europe as a grad student in 2013, it was the momo, not the food that I ate at home, that I missed most—the moments spent consuming momos in streetside nooks, watching scenes in my city unfold.

In Western Europe, Asian foods, like others of non-Euro-centric origins, remain curtailed by limitations of European appetites and aesthetics. When I lived on the continent, my experiences eating Asian food were defined by the pallid demeanor of unwelcomeness granted to far-away cuisines. Tibetan food, meanwhile, was mostly absent, often clubbed together with Nepalese or Chinese cuisines and housed under the garb of “Himalayan:” a gesture evoking the sentiments of tranquility, meditation, and travel through which white people comfortably approach various parts of the world. The Tibetan restaurants I did encounter became a reminder of the restaurants I would visit in university in Delhi, where Tibetans not only taught me the act of dissent and protest, but also how their cultures move, adapt, and survive.

Half a decade after my own lived experience in Europe, I wanted to know more about the distinct journeys of Tibetans in the European continent and how the momo has adapted along with them. Ahead, meet the proprietors behind three Tibetan restaurants across the United Kingdom and Western Europe, where many Tibetans—and others warmed by their hospitality—take comfort away from home.

Yeshi Jampa first learned how to make momos while growing up in a mountain-dwelling community in Eastern Tibet, where he and his father spent their days on high altitude pastures alongside their herds. Yak meat momos were the most common. “The young people would knead the dough and then adults would prepare the meat or vegetables,” he says. He remembered that his elders shredded the vegetables by hand, as “using a knife would make them tough,” and that they would all sit around the fire together as they prepared the food. “Fire is central to Tibetan cuisine,” he says. “Life happens around it.”

In the late ‘90s, Yeshi and his family walked across the Himalayas and arrived in

Dharamshala, India, as refugees. In 2009, he met Julie Kleeman, a visiting

Beijing-based British expat, on the side of the road. “We were both watching

mountain langurs and we got talking,” Julie says. It was winter, and very cold. “The first meal Yeshi cooked me was beef thenthuk—a hot soup with flat, handmade noodles,” she says. “I needed hot food—Yeshi's cooking brought me back to life.”

Two years after Julie and Yeshi met, they moved to Oxford, where Julie started working for Oxford University Press. It was difficult for Yeshi to find work, so he decided to take matters into his own hands, serving the homemade momos that had been a hit with friends and family to the public via a momo stall at a local market in Oxford, where they were also a hit.

In 2020, Taste Tibet became a brick-and-mortar location. Yeshi is the restaurant’s head chef and makes everything from scratch, while Julie manages and guides the operations. “We have a small team and a close-knit clientele. We like it that way,” Yeshi says.

The restaurant’s best-selling dishes are their momos, which they make with fillings of fresh seasonal vegetables or beef, and serve with their house Sepen hot sauce as well as condiments like pickled mooli radish. They sell hundreds a day. “When we cater at music festivals, we shift thousands and thousands of momos a day,” Julie says.

Although they now cook for so many Brits, Julie and Yeshi told me that British people, like many of us, don’t know much about Tibet. “There are only some 800 Tibetans at most in the UK, and it is hard to get information out of Tibet,” Julie says. Under China, Tibetan culture is rapidly disappearing, and to cook Tibetan cuisine is to resist that erasure.

“When we cater festivals like Glastonbury, we have the opportunity to reach so many people, and we also put out a weekly blog on our website about Tibetan culture,” Julie says. Yeshi’s nomadic-pastoralist ancestors cooked for sustenance and survival; for Yeshi, food played the same role as he moved to India and later Britain. “In Tibetan culture, people most revere those who work for the benefit of others,” Yeshi says. “Far away from Tibet, cooking helps me to continue serving my community, and to keep Tibetans' ways of life alive.”

Mo Mo is located in the neighborhood of St. Gilles, nestled between French coffee shops and upmarket delicatessens. It is barely noon when I visit, but diners are already queuing up to order. The restaurant interior is colorful, comfortable, and warm, with a small terrace for rare warm weather in the rainy European capital. “You are lucky, it is sunny in Brussels!” Lhamo Svaluto tells me as I arrive, and she gestures to her staff to set out a table for me outside. “But all weather is good momo weather, anyway.”

The restaurant has a small, fixed menu, with the most popular offering being the vegan “momo set,” in which hot, handmade vegetarian momos—filled with vegetables like potatoes, shiitake, and cabbage—are served with a salad, a portion of soup made with coconut milk and barley, and sides of soy and tomato-chili sauces. “These aren’t traditional momos. Traditional momos are made with meat, of course, but I needed to have a niche, and there’s not too many vegan restaurants in Brussels,” Lhamo says. A recent menu addition is a “momo in salad,” inspired by one of Lhamo’s favorite foods: the Vietnamese dish bun-cha.

Lhamo was born in Bhutan to Tibetan parents. She was adopted as a child by a Belgian couple and grew up in Brussels. “Like my restaurant, I am Bruxellois, too, but if you think ‘Belgian capital’ would you think of me?” she says rhetorically, pouring us tea.

Growing up in Belgium, she ate Belgian food at home but was also aware of

belonging to a culture in which many live in exile or under foreign rule. When she visited her birth family in India, she would cook with them. Soon, food became a way to communicate with other Tibetans, all with different histories and paths,

distinct but united by love for their people. “It was challenging, to navigate all these things, express all of it to myself,” she says. “But I found a way, and food was important here. It was through cooking and eating momos that I understood parts of myself.”

The momos served at Mo Mo are made by an all-Tibetan staff of immigrants or

asylum-seekers who are now gainfully employed with the restaurant. “For me, it is

important to give Tibetans community here. We don’t have many Tibetan clientele, but for the staff, it needs to be a good place of work,” Lhamo says. This is why she keeps her menu small and why the restaurant closes for two days a week.

Even as the Tibetan community grows in Belgium, Lhamo notes that there are close to no Tibetan restaurants in Brussels. “There are Indian and Nepalese spots, but no Tibetan ones,” Lhamo says. “People don’t know what Tibetans eat. So I also wanted to bring awareness to that when I opened the restaurant.” Lhamo says that dumplings do prove to be a useful genre. “In Brussels, people know pierogi, the Polish dumpling, and some people know gyoza, and to introduce them to a different kind of one was not so hard.”

It is fitting that Down to Earth is frequented by students in Cologne—its interior, with wooden tables, low-hanging trees, and lanterns, would be right at home in Dharamshala, and the restaurant reminds me of the momo shops where I’d spend time while at university in Delhi.

Teki, who is from the Amdo region of Eastern Tibet, met friend and

co-founder Leon Krupfahl in 2018, when they became flatmates. The two had an “immediate bond,” Leon says, and Teki soon introduced him to Tibetan food through the momos and handmade noodles that he’d cook for their friends. “It was amazing food—so nourishing and filling, and so delicious,” he says. Leon’s prior restaurant training was as a cook in “classic, chef-run kitchens” in Canada. “It was great, I learned a lot, but I wanted to do something more cozy, more intimate. And Teki’s food was exactly that,” he says. Teki, meanwhile, had previously worked in sushi restaurants. As a young Tibetan immigrant to Europe, he didn’t see his culture’s food reflected anywhere. “In Europe, I cooked to remember my home, and everyone loved the food, so we thought it would be a good idea to introduce people in Cologne to this cooking,” he says.

The menu reflects Teki’s upbringing as well as the way in which he cooks for friends: fluffy soup momos filled with flavorful beef or vegetables, handmade noodles in thick broths, sharp and pungent chili sauce. “The momos are to share,” Teki says. “The idea of ‘sharing plates,’ did you know this before? Isn’t everything a sharing plate?” he adds; I laugh, remembering my own confusion around Europeans not automatically sharing food. The restaurant sells around 150 to 200 momos a day, and Teki arrives to the restarant daily at 6 a.m. to prepare them. He and Leon, who arrives later in the day, ensure that the shifts are balanced and circular for the rest of the staff. “No one should be so tired that it is not fun to work anymore,” Teki says.

The restaurant opened during the Covid-19 pandemic, which was tricky for the duo to navigate. “But we were lucky, we had patronage from the start. People really supported us,” Leon says. Today, the restaurant is always full. “It also helps that the city is full of students and young people. Young diners are more

adventurous than older diners in Germany,” Leon says. The camaraderie between Teki and Leon transfers to the filling and juicy momos and the rich, flavorful broths. Eating at Down to Earth feels like being fed by a close friend on a day you have a terrible hangover.

Despite his well-loved menu, Teki is eager to experiment more. He and Leon recently went on a motorcycle trip in India, where they gleaned a wealth of inspiration. “For me, adventure is important. I don’t like this idea that, because I am Tibetan, I should always be ‘traditional,’” he says. “I want to do different things, but to encourage that sense of warmth from my Tibetan community. People need that here.”

Sharanya Deepak is a writer and editor based in New Delhi, India focused on food, language, and the commodification of culture. She's an editor at the food and culture publication Vittles.

Tenzin Tsering is an illustrator based in Toronto. She loves comics, characters, and color, which is reflected in her work, and she enjoys exploring the roots of her Tibetan and Filipino heritage.

Above the Fold was created by Leah Mennies