Interview #17: Graeme & Caitlin Miller's Knishes

The duo behind Portland, Maine-based BenReuben's Knishery talk round vs. square shapes, knish geography, and the beauty and challenges of going starch on starch.

Welcome to Above the Fold, a newsletter all about dumplings + the people who make them. Like what you see? Smash that subscribe button! (Or delicately click it, that works too.)

Grame and Caitlin Miller grew up eating knish at Jewish delis, but it was always as an add-on. “As a side dish—I think that’s how most people think of them,” Caitlin says. “Something you add to what you’re going to the Jewish deli for.”

While Graeme was working at the popular Portland, Maine-based Eventide Oyster Co. as chef de cuisine, he would make the 100-mile trek down Route 1 to Evan’s New York Deli in Marblehead, Massachusetts every time he craved a deli fix. “I thought, being a chef, I shouldn’t have to drive a hundred miles to get the food that I want,” Graeme says. “I’m a little more capable than that.”

So he started tinkering with a potato knish on the side. “After I made it once, I just remember thinking I could put a lot more than just potato inside of this,” he says.

By late 2019, Graeme and Caitlin—who was the director of HR for Big Tree Hospitality Group—were planning a Jewish deli of their own, inspired by the couple’s Jewish heritage and families. (Graeme’s father’s Hebrew name is Reuben, and Ben Reuben is Hebrew for “son of Reuben.”) While the original plan was to go all-in on sandwiches and sides, with knish in their standard add-on role, they soon began to think smaller on deli, and bigger on knishes.

“When Graeme started creating the knishes, he was playing around with different flavors. It just sort of occurred to me, as I ate one stuffed with pastrami and mustard, that I didn't really need a pastrami sandwich in addition to that,” Caitlin says.

“There are lots of different places to get sandwiches around, but nowhere up here at least to get knishes and really, even beyond that, ones that are the way that Graeme is making them, where they're stuffed with lots of different flavors.”

As BenReuben’s Knishery heads into their second Portland, Maine summer, read below to learn more about the knish R&D process, getting creative with the humble potato, and the difference between a Boston knish and a California knish (knish geography: it’s real!).

When you first started developing your knishes, what were you looking to achieve? What were you trying to maintain in the version of the recipe you were creating?

Graeme: Knishes have such a wide umbrella of classifications within Eastern Europe. As far as Poland to Lithuania and all the way across to the Baltic Sea, people are eating knish. You have so many different cultures interpreting that, and then different families interpreting that as well.

The ones I grew up with were a lot more like pastry dough-oriented knish. The ones I started to work on initially as a chef were a little more bread-oriented. A little more of an enriched dough. The beautiful part about knish is that they are an interpreted depending on region and family.

There was definitely a lot of consideration in regards to what I was looking for. I knew I liked a flaky, warm crust with a good crackle to it. I also needed the dough to be able to be stretched really long and wide for rolling purposes. It was a bit of a culinary experience to build our current dough for knish, but a lot of it is founded on tradition and older or Old World recipes.

Knish traditionally are filled with potato, rutabaga, ground beef, or kasha, and people really didn't step outside of those four options. My generation and the generations below me don't really know what a knish is and haven't really gotten a chance to experience this type of food as much as I did when I was a kid. Caitlin and I both agreed that we liked bringing those types of things back, but in moderation.

Caitlin: Being inspired by what comes from Maine wherever we can, they are usually changing seasonally. But also, we didn't want it to just be stuck in Eastern Europe. Because being Jewish, as we know, is not only an ethnicity, it's a religion that can exist anywhere in the world. We just feel like the fillings give us that space to explore flavors from around the world—and then have fun with it. Graeme did a buffalo chicken knish for the Super Bowl, so we can also just go very current and have fun with it for holidays and events and things like that.

Can you share some other examples of fillings you've done and highlight some favorites or ones that have been particularly popular?

Graeme: We generally have five to six different varieties of knish available at a given time. We have some of what we call our pillars.

Caitlin: Well, the Everything and the BenReuben are definitely our two top sellers. The BenReuben is a play on a Reuben. It's pastrami beef and sauerkraut and Swiss cheese. Though, of course, we do a somewhat kosher version without the cheese—I don't mix meat and cheese. You can get Thousand Island on the side to dip it in, which is such a traditional Jewish deli thing.

Same with the Everything, which is potato and cream cheese and scallion on the inside. It's sort of our play on the potato. We have a “smoked salmon-aise” sauce on the side to dip into. It's supposed to remind you of eating an everything bagel with scallion, cream cheese, and lox on it.

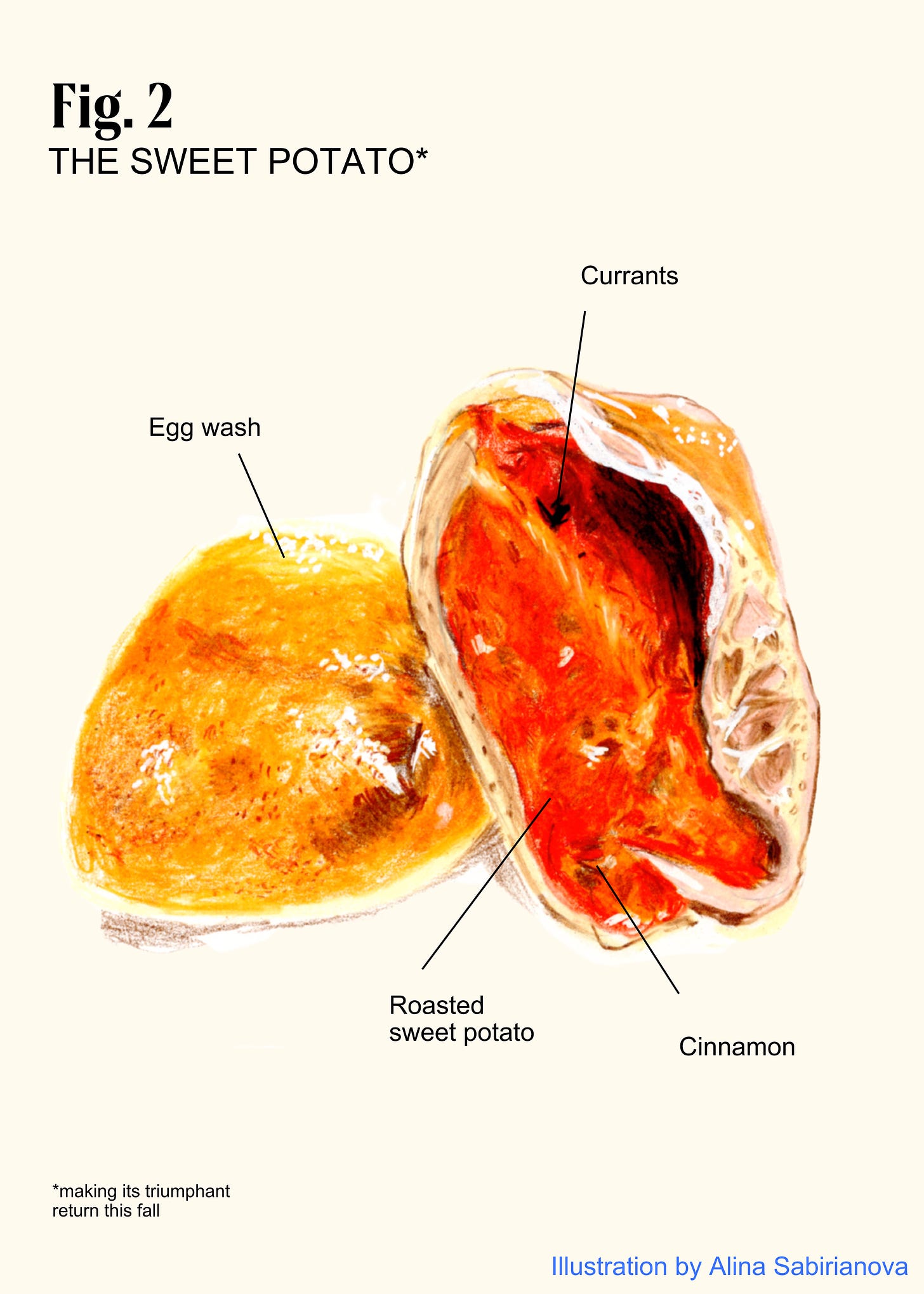

And then there’s the sweet potato. That's another sort of traditional Jewish dish. It's sweet potato cooked with prunes, apricots, or currants and cinnamon. That's one we usually have in the fall and winter.

Caitlin: There's definitely a following for the white fish, which is not your traditional Jewish white fish. The filling is an adaptation of a Portuguese Bacalao fritter and a French Brandade, made with Casco Bay white fish. It changes between pollock or hake or haddock, and that’s mixed with potato and lemon and herbs. When people come in, if the white fish is sold out, there's a lot of disappointment there.

I think the most remarkable thing is when people come in and we hit a moment of heart together. For example, we once had two sisters come in and say they hadn't had a knish since their father passed away. They ate the white fish knish and were in tears just sort of remembering their father together.

Once you had the epiphany moment that knish could be the central component of your business, where did things go from there?

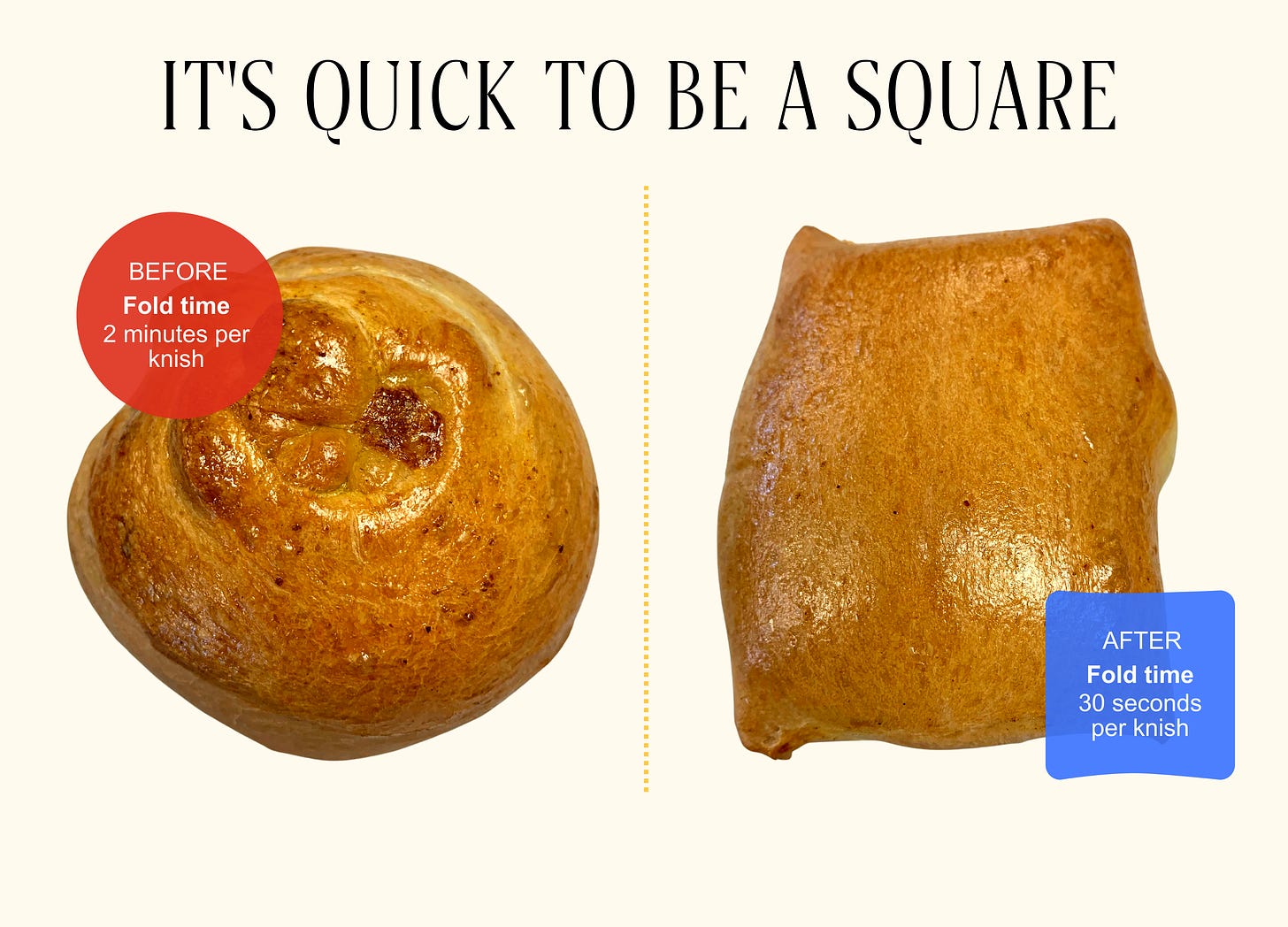

Caitlin: Graeme was originally hand-wrapping each knish. Maybe you can get into it a little more, Graeme, but he would... How long did it take to make one knish the way you used to roll them?

Graeme: About two minutes per knish.

Caitlin: Two minutes per knish. So no matter how many hours he was working, and for how much you can sell a knish for the way we want to, which is for people to come in and feel like they can buy lunch for a really affordable price for really good food, we were running out of knish every single day. The demand was high, but no matter how long he stayed, how many he rolled, if you think about it, two minutes per knish, there was just no way he could keep up.

So, we shut down for a few days after we had opened and we rearranged the shop and Graeme found a new way. If you look at very early pictures, they're sort of wrapped and they stood up tall and they were open with a hole at the top, which is one traditional way to do it.

Graeme: That was how I originally learned, yeah.

Caitlin: I mean, they were beautifully hand-wrapped, but then...how long do they take the way you do it now?

Graeme: About 30 seconds.

Caitlin: 30 seconds per knish. So, now he can roll them all out and cut them. They're now rectangular—I almost think of them more like a hot pocket shape, which personally I think are much easier to eat. Our production went so much higher just with that one little change.

How did you decide on the more hot pocket shape? Were you kind of experimenting with a few different things until you were like, okay, this is going to work?

Graeme: There's two ways of making a knish. There's a round knish and there's a square knish. The round knish is a little more Old World. The ones that are wrapped around the filling and left open on the top. The square ones were really introduced through the Industrial Revolution and the introduction of machine-made knish, where the dough was able to mix itself, come out of a hopper, run along a roller, and they were able to just fill and mass produce knish. That's where the introduction of a street vending knish came along. They're all fried and they're square.

We are adamant about hand rolling all of our knish, so we had to change the dough a bit to be able to accommodate the type of stretch that we have to provide on the table. And the way of doing it is pretty traditional. I didn't have to really invent very much in regards to the square knish. You just had to choose either round or square. The rest is pretty straightforward.

You roll the dough out into baguettes, basically, and then you roll the pin over them flat and then you can grab either end of the dough and stretch it. You stretch it outward, when the dough is relaxed, upward of six to seven feet. And then we take our rolling pin back over the stretched dough.

We shoot for a dough width that’s about six inches wide. And then we go through with a scoop of the filling. Some fillings are a lot easier than others. Our Everything one is like the ideal filling for knish because it just stands upright. It's not too wet. It's not too dry. But you get into ones like the cinnamon sweet potato, and that one tends to weep a little bit more. It tends to be a faster type of production in regards to those so that the dough doesn't get too wet.

Then you fold over once. We crimp. We fold over a second time to kind of close up the knish itself. And then we crimp and cut between each one. It's about four inches between each knish. Once we're done crimping and cutting, we're able to get them on the trays. We egg wash them and then we mark them.

For the buffalo chicken one that we did for the Super Bowl, we put celery salt over the top of it. Our white fish gets paprika over it. The Reuben gets pastrami spice over the top. This helps mark which knish is which but also gives a little bit more to the knishes themselves.

When you made that switch, did that make a difference with customers?

Graeme: An astounding revelation to opening BenReuben's is just how grateful people are that we're here. And so the transition from round to square was very minimal. Nobody really paid much mind to it, other than we've had them more readily available for them.

Caitlin: I don't remember very many people saying anything at all. The comment we sometimes get are, "These don't look like the knishes I know." And Graeme is so good at being like, "You must be from..."

Graeme: Yeah, knish geography is a real thing. Every region in America seemingly has a different type of knish, from New York and New Jersey to Boston. Philly has a different type of knish. LA has a different type of knish. Generally, yeah, you can tell just by the way people come in and react to ours. I can generally make probably about an 85% guess on where they are from just by their responses.

Not to get too much into the weeds, but also because I can't help myself. What would be a Philly style and what would be Boston style, for example?

Graeme: The Boston ones are... technically, they're either called Boston knish or cocktail knish. They're generally about half the size of ours. Something that you'd see passed as hors d'oeuvres. And then a Philly one tends to be a different type of pastry. They'll come in and they'll say, "Those don't look like mine."

That usually is the red flag for Philly because they tend to be a little more of a pastry-oriented, phyllo dough type of one. Same with New York. They'll come in and they'll either just straight up say, "These aren't Yonah Schimmel's," which is a pretty obvious regional one from New York, or they say, "These aren't potato knish," or, "Do you have just plain potato knish?" They're usually looking for square, fried ones. Something that a street vendor would have.

Apparently, none of my knish fit into any of these regions. We're apparently creating a Maine variety of knish.

I'm Jewish and I didn't grow up eating knish that often. It was also like your experience, where it was a thing that was also there on the table. But I had mentioned that I’d be doing this interview to my mom, and she was like, "You know, it's just so much starch. It's just starch and potato." That was her first comment. It sounds like you don't have one that is straight up just potato, and I'm curious if that was deliberate.

Graeme: 100% percent. I share the exact same sentiment as your mom. Almost every traditional knish is like potato or rutabaga or kasha. In the Old World, you didn't have very much. You had potatoes, you had rutabaga, you had some flour, and therefore you could do these things—that's how pierogis came about.

And to kind of stand on their shoulders in a sense and be grateful for what we have, we have more than just potatoes and rutabaga. We're blessed with the opportunity to put more than just that inside of our knish.

Caitlin: We do get people who really do just want plain potato, and we will make them with 48 hours notice—I think you've also done plain ground beef ones. And we do get a lot of questions for kasha knish. I know my mom was like, "You need to have a plain potato knish."

For the first few months when we opened, people were coming in for a plain potato knish and it took everyone a while to get to know us and what we were trying to do and that's when we were like, of course, we'll make it for you, but try what we have. We're not trying to be better than the traditional potato knishes that you can get in New York or all these places that Graeme named, but we will be happy to do it for you.

At one point your dad was also working with you. Is that still the case?

Graeme: Yes, very much so. He works two days a week with me. He'll be on for two days a week until he says no more.

Is he making knish?

Graeme: No. I tend to keep him away from that type of work. Not that he's not capable, but it's labor-heavy stuff and with my father being 70 years old, he doesn't need to do anymore than he already has in life. He makes incredible rugelach.

My father isn't a pastry chef, he's a pediatrician. When I give him a recipe, he follows it to the simplest of measures, which is very similar to how my great-grandmother would have approached it as well. And so, in a sense, I'm able to transfer a bit of alchemy from my father into the food.

He also works our counter quite a bit. I love having him talk to the guests. He gets a kick out of having a great relationship with the community as a former pediatrician. That's something that he enjoyed very much about his career and gets to live it a little bit more here at BenReuben's.

That sounds, quite literally, like my dad's dream. He's gotten very into baking during retirement, and he keeps hinting that he wants one of us to open a bakery so he can just take on shifts whenever he wants.

Graeme: Send him up to Portland.

You can have a parental internship program.

Graeme: That's a great idea.

Above the Fold was created by Leah Mennies. Logo + design elements by Claudia Mak.

The above interview was condensed and edited. Interview subjects are paid an honorarium for taking the time to share their knowledge and experience.

Love 💕

Way coolio!