Interview: Talking Dumplings with Polina Chesnakova

The author of Chesnok discusses the family memories, historical research, and dumpling R&D that went into her deeply personal cookbook.

I am so excited to share an interview with food writer and cookbook author Polina Chesnakova, who recently released Chesnok: an expansive collection of recipes from what she calls “my corner of the diaspora,” comprising Eastern Europe, The Caucasus, and Central Asia. As she shares in the introduction, Polina’s own family spans all three; she was born in Ukraine and was raised in Rhode Island to Russian and Armenian parents who married (and for a time, lived) in Georgia.

“Chesnok—its recipes, anecdotes, and essays—doesn’t represent only my family’s heritage. It’s an invitation to sit at, and experience, the breadth and nuance of the post-Soviet table, as well as the spirit of warmth and generosity at its heart,” she writes. “My aim is not to perpetuate a simplistic monolith of the Soviet legacy, but to speak to a diaspora of people who still live with and navigate its complexities and contradictions.”

Chesnok is not a dumpling book (and to that end, I have the Uzbek plov, soup-lapsha, and syrniki bookmarked to make this winter), but it’s not not. The regions covered in this book all have deep dough-wrapped-filling traditions, and many of these are honored in the “dumplings, pastries, and breads” section of the book, which features Polina’s carefully documented and honed recipes for varenyky, pelmeni, khinkali, and dumpling-adjacent (and for Above the Fold’s purposes, still highly-relevant) pirozhki (stuffed buns) and treugolniki (beef turnovers).

We caught up on a call a couple of weeks back to discuss these in more detail— Polina was incredibly generous to take time to chat on a break from a multi-city book tour that she traversed with her almost-4-year-old and 4-month old in tow. Learn more ahead about her thoughtful, considered approach to framing the narrative of the book—and the number of tries it took for her to nail her khinkali recipe.

But first: In case you still have holiday gift-gathering to do: I will be doing my final post-office run of the year FRIDAY (12/19). And, tbh, I can’t *guarantee* that even those will arrive pre-12/25 as I’ll be at the whims of the USPS. But after Friday, orders won’t ship until the week of 1/12, because yours truly will be OOO!

As a reminder, the following (and more) is still up for grabs:

The Above the Fold starter pack bundle: Issues 1 + 2, a set of 3 notecards, and a riso print, $50 ($67 value)

I’m down to two Above the Fold(er)s! A riso-printed special edition folder packed with a bookmark, recipe card, two riso prints, and, of course, Issue 2 of the print mag. 50% of all proceeds go to Undocumented Women’s Fund

The Dumpling of the USA Map! 100% of proceeds go to Undocumented Women’s Fund

To the interview!

Leah: In the introduction of the book, you wrote that the book is deliberately not “Russian-ish” or “Georgian with a twist.” Why was that the direction that felt right for this project?

Polina: The initial goal with the book has always been to preserve and document my family’s recipes. Because I came to them as a novice—my mom and my aunts would get together, they would teach me how to make everything. And it was one thing to make it with them. It’s another to truly internalize it, go into my own kitchen, and re-create it. I wanted to build a really strong base of knowledge for myself, and have recipes that I can come back to again and again.

For all the recipes in the book, [the goal was to] document them the way that my mom and aunts make them, because if I don’t, they’ll be lost with that generation. And in doing so, it was also like capturing this like canon of recipes that everyone in the diaspora sort of is familiar with and knows and shares. If you walk into Tashkent Market in New York City or any big Eastern European store with a hot bar, it’s all these dishes that anyone that grew up in our community is familiar with. There hasn’t really been a book that documents them.

And so the same goes with the dumplings. It was like, okay, if I can teach myself how to make these dumplings in their most traditional form, then I can, down the road, play around with them.

You’re bringing me to another question I had—in the introduction for the khinkali recipe you share in the book, you write about a turning point in 2015 after you visited Georgia, where you decided that you had to craft ones that rose to the standard of the ones you tried there.

That was of course a grand goal—but I think it also speaks to that foundation-building that you’re speaking of. It’s been a decade since that moment happened, and you have this really beautiful recipe in the book. What was the recipe development process like over the years, and when did you say Okay, I’ve gotten there?

That’s a great question, because my mom and my aunts, their approach to cooking is that everything’s done by eye and by feel, and I make dumplings with them not really truly understanding why things were done the way they are. They would make the meat filling and they would knead it. And I didn’t really think about why they would knead it, or for how long.

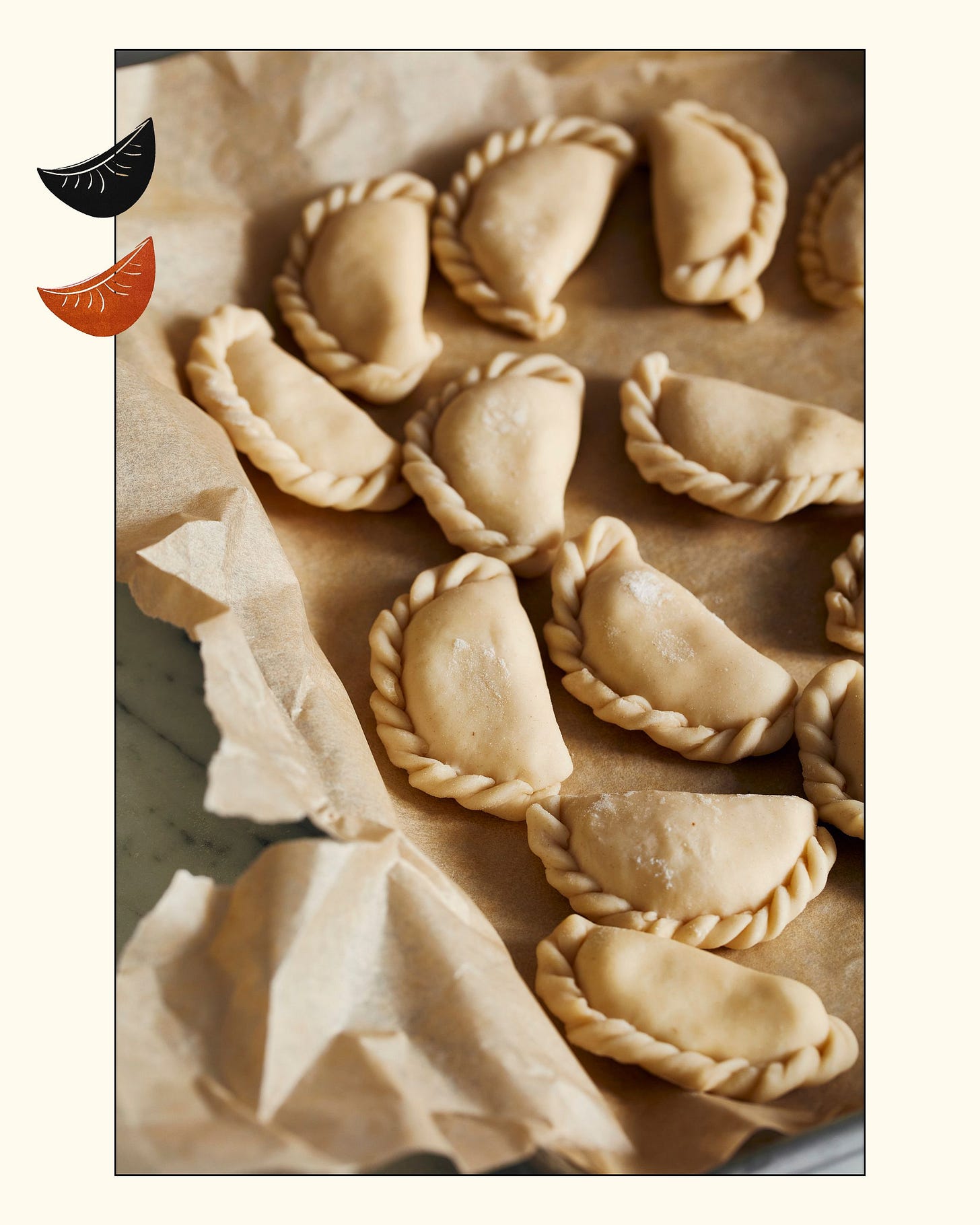

So the khinkali are something that I’ve had to hone or practice over and over. It started out with the dough—sometimes I’d make it and the dough wouldn’t really hold its shape. I learned I had to do a little less water or use really cold water to give it a firm texture. With the filling, sometimes it felt like the texture was kind of mealy or it’d sort of fall apart. And it wasn’t until after a few rounds and, and some research that I was like, oh, I need to knead this, which is what my mom and aunts were always doing. I learned, oh, by kneading the mixture, you’re rearranging proteins, and integrating the fat, and you get this really pleasantly bouncy texture to the filling.

I had a blueprint from my mom and aunts, but I had to go through this R&D process to relearn it to get to an end result I was really happy about. It’s taken me many, many batches of khinkali to get to a dough that I’m really happy with, with a meat filling that has the right texture and flavor.

I’m thinking about how much practice and labor and effort and time that goes into developing a recipe for just one dumpling—the region that you’re covering is one of the most richly varied when it comes to the world of dumplings. How did decide which ones you’d share recipes for in the book? Was that more tethered to ones that you had a deep personal connection to?

Yes, absolutely. The khinkali, the pelmeni, the varenyky, those were dumplings that I grew up on. And I knew that I had to document them. The khinkali, the varenyky we would make at home; you walk into an Eastern European store, and there’s always a chest freezer full of pelmeni so you can pick up a bag. But I can’t write a cookbook that just says go to the store and pick them up.

And there’s something communal about dumpling-making, too. We would come together, my mom, my aunts, and my cousins, and we’d make a whole afternoon out of them. We would sit down to dumplings and then we’d all take home bags of them to stash in our freezer for later on.

I was just at Brighton Beach and I went to an Uyghur restaurant and they had these beautiful manti—they’re delicious, but they weren’t something that I ate often, at least in my family or my community. It wasn’t something that we made in our own homes. And that was sort of how I filtered which recipes went into the book, ‘cause, I could have written a book that was twice the size that would encompass all the recipes from all of these countries that used to be part of the Soviet Union. But ultimately the book is through the lens of my family and the dishes that we made.

I linked in an earlier newsletter to this Bloomberg piece that you wrote that was such a deeply researched, interesting piece around the use of a cookbook as propaganda in Soviet-era Russia. There are a lot of really thoughtful introductions and essays in your book. How do you balance external research versus primary sources?

I’m someone who can go down a research rabbit hole to the point where it takes me so far away from where I’ve started that I’m like what am I even trying to do here anymore? And so I’m curious how you navigate that.

The nice thing about writing for a physical book is that you are limited in space. Online you can go on and on, right? But you have one page, essentially, to write a recipe. So you have to be very intentional about what information you introduce about each one. I came to each recipe thinking, okay, what’s the hook here? What is the most interesting thing about this recipe? Sometimes it was a personal story, but then sometimes it was historical or purely educational.

Khinkali, for instance, every time I think about them, I think about this trip to Pasanauri and driving down the Georgian Military Highway, whereas varenyky takes me back to childhood memories, eating them on the floor of my Ukrainian friend’s house. When I finished writing the book, I looked back and it ended up being this really nice balance of historical, educational, and personal.

Obviously dumplings—the varenyky—are on the cover of the book. Was that always the vision, or did that come later when you were going through the photos and it was just like, oh, we want this one?

So much of the challenge of this book—and especially around the packaging of the book— was that it’s food for the Soviet diaspora. I didn’t want to anchor it in one culture or cuisine or language. So originally, I really wanted to do the holiday spread from the beginning of the book, because it showcases all of these different dishes from different cuisines that make up my family’s table. But from a design and visual perspective, it was just too busy. You really want a cover that is eye-catching. We needed one hero dish.

We considered the chicken noodle soup, but kept going back to the dumpling photo. It was just so evocative and had such a strong sense of place. I was a little nervous to put a Ukrainian dish on a cookbook that’s not Ukrainian, but at the same time, I think anyone in the diaspora would tell you that they probably have some warm memory of eating them. So it speaks to a dish that is steeped in very strong Ukrainian traditions, but at the same time it’s shared by all these people from all of these different countries.

I don’t know if you’re fully on the other side of book-touring, but you have quite a bit under your belt. By now, you’ve had so many interactions with people who are actually experiencing the book. I’m curious what that has been like.

In the lead up, there was definitely an element of nervousness because the region that I’m writing about, this diaspora, especially since Russia invaded Ukraine, has been so politically charged and there are so many emotions and really deep feelings. I wasn’t sure how people would react. But since the book has come out, I’ve had an outpouring of messages from people who are thanking me for writing about their immigrant experience. Because there really hasn’t been a book up until this point that has written about it.

There is Kachka from Bonnie Frumkin Morales, but it’s a restaurant cookbook. She brings in a lot of the personal, and it’s one of my favorite books. But ultimately it’s a book about the restaurant, whereas this is almost a cookbook-meets-memoir. And I really wanted to write about this diaspora that has been traditionally kind of overlooked or misunderstood, or are just misinterpreted. Many people feel very seen and validated and at the same time, like all of a sudden now they have this canon of recipes that they also grew up with but might not have written down recipes for.

Is there a dumpling recipe in the book that you feel particularly attached to? Is there one that you actually tend to make most often?

I would say the answer for both is definitely the khinkali, just because I’ve taught it so many times and it’s the dumpling that my family makes most often at home. And then kind of speaking back to your R&D question, it’s the one recipe that I really found the most growth in—the one that I was making and teaching in 2016 is so different from the one that I did today. There have been many years of learning and practicing that went into this final recipe.

Interview has been condensed and edited.

The kneading insight for khinkali filling is gold. I think a lot of us dunno why our family members do certain steps in traditional recipes, and seeing that R&D process where she had to reverse-engineer her own familys techniques really shows the gap between watching and understanding. Ive been tryng to document my grandmas pierogi technique before its too late, and this makes me realize i need to ask more why questions instead of just filming her hands.